Throughout Irish history, the spectre of absentee landlords has cast a long shadow, leaving a trail of neglect and suffering in its wake. From the days of foreign landlords who resided far from their Irish estates, leaving tenants to endure dire conditions, to the more recent emergence of vulture funds, the plight of Irish homeowners has once again become a grave concern.

Historic Resonance

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries land belonging to Ireland’s Catholic majority was plundered and handed over to foreign landlords primarily of Anglo Protestant stock cementing a Protestant Ascendancy for years to come. Many of these landlords remained in their salubrious overseas surroundings in England, Scotland and Wales whilst their Irish tenants faced impoverished and dire conditions. Thus, the term ‘absentee landlords’ was christened imbuing a sense of neglect amongst the old Irish.

The situation was worsened by the fact that thousands of pounds, some estimate circa £800,000, was transferred to these ghostlike overseas landlords leading notable Member of Parliament (MP) Henry Grattan to propose a remittance tax.

Many of these landlords utilised unscrupulous middle men to rent out land to already indebted smallholding tenants. Statutes such as the Poor Law slapped taxes on landlords who had tenants paying less than £4 per annum forcing already pauperised tenants to be evicted or in some cases exiled to America.

These dire straits were exacerbated following the imposition of the Act of Union (1801) which saw the College Green parliament, made up of Protestant gentry, deemed impotent thus rendering Grattan’s patriotic movement for parliamentary sovereignty null and void.

Many parliamentarians fled Dublin seeing no reason to remain in a city with no functioning or legitimate seat of government. Thus, the preponderance of absentee landlords increased. It is estimated that in the 1800s there were 10,000 absentee landlords based primarily in London - where Irish MPs now served.

When push came to shove in 1845 with the arrival of the potato blight culminating in the Great Hunger, Ireland, whilst remaining a net exporter of foodstuffs, was left asunder to the ravages of extreme hunger and mass emigration. Over a million Irish perished with landlords continuing to evict tenants in droves.

The land issue was central to Irish anxiety regarding its perilous position within the United Kingdom. The Land League along with Charles Stewart Parnell’s crusade and the boycott movement - a word invented in Ireland - helped propel the issue to importance in Westminster with a series of remedying acts passed including Wyndham’s Act 1903.

The most infamous absentee landlord Charles Cunningham Boycott

With the act, the government agreed to buy out landlords while tenants were given their former land and now considered independent proprietors. These purchasers were provided with long term govt loans with repayments spaced out in increments over a period of 35 years at a lower rate than previous rents thus undoing a large part of the Cromwellian land settlement of the 1650s.

Modern Absentee Landlords

Fast forward to the present, and a new breed of absentee landlords has emerged in the form of vulture funds.

The names of these funds span from the mundane Pepper Finance to the rather menacing sounding Cerberus, named after the three headed dog of the Roman underworld.

More than 2,000 Irish households were banished to Hades after Cerberus acquired a bulk of loans from the now exited Ulster Bank in 2018 following ECB guidance to unload supposedly bad loans. At the time Fianna Fáil’s Michael McGrath decried the move as an attempt by the bank to outsource their “dirty work to a US vulture fund.”

The same year saw campaigner David Hall of the Irish Mortgage Holders Organisation (IMHO) warn of civil resistance following the export of 10,000 PermanentTSB home loans - 1,000 of which were performing - to Start Mortgages which is linked to the Lone Star vulture fund.

Despite the state having a majority stake in the bank, ministers expressed reservations regarding the sale proving once more how powerless they are to the whims of Frankfurt dictates. These are the same ministers who stood idly by while banks overcharged customers with tracker mortgages.

Hall elaborated: “One woman in touch with me who owes less than €3,000 on her mortgage and within that there’s a few hundred euro of arrears and they have sold this lone to Lone Star and she’s worried she’ll lose her house.”

Is there a political appetite for a Nama 2.0?

While the issue of mortgage arrears should of course be addressed the fact is that such missed payments are a relic of the housing bonanza that occurred during the Celtic Tiger. Thousands of people were provided with loans on homes the banks and developers knew they couldn’t afford in order to prop up the lucrative subprime mortgage market in which those at the top profited from.

The man who invited the vultures to feast on these vulnerable customers was then finance minister Fine Gael’s Michael Noonan. From 2013-14 he convened with private equity vulture firms in eight different meetings whilst refusing to meet with mortgage advocacy groups. As a result €300 billion in property assets were snatched by these vultures with many Irish families resting in their nests just waiting to be eaten.

Displaying all the hallmarks of Diarmuid MacMurrough who invited the Normans into Hibernia in the 12th century, Noonan has been dubbed a ‘vulture lover’ for, inter alia, refusing to adequately amend Section 110 that allows Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) to avoid Irish taxes. This modification gave the vultures a free meal of distressed assets that would otherwise have cost €80 billion.

While Gen Z and Millennials are facing Himalayan rents, the vultures are making millions whilst paying less than €300 in taxes.

Most of these assets were acquired when interest rates were at near zero, allowing them to purchase at a discount. With the current ECB lending rate hovering above 3 per cent many non-bank mortgage holders are staring down the barrel of unsustainable monthly payments.

While mortgage rates have gradually fallen from their recent highs for those banking with AIB, BOI and PTSB, non-bank lenders such as Pepper Finance are raising their rates.

Why?

Because these non-bank operators do not fund themselves the same way regular banks do.

While banks are funded through customer savings, in a process known as fractional reserve lending, the non-bank sector is funded by borrowed money which is currently more expensive. Invariably these costs will be passed onto non-bank mortgage holders through no fault of their own.

It is estimated that are 113,856 loans held by non-bank entities in the State.

These customers deserve better.

It is vital that the government demand the main lenders, who are profiting off the back of recent rate hikes, take back their former customers with whom have the means to pay the ‘normal’ mortgage rate.

It’s time for a Wyndham’s Act for 2023!

The patience of the Irish public with their banks is wearing thin.

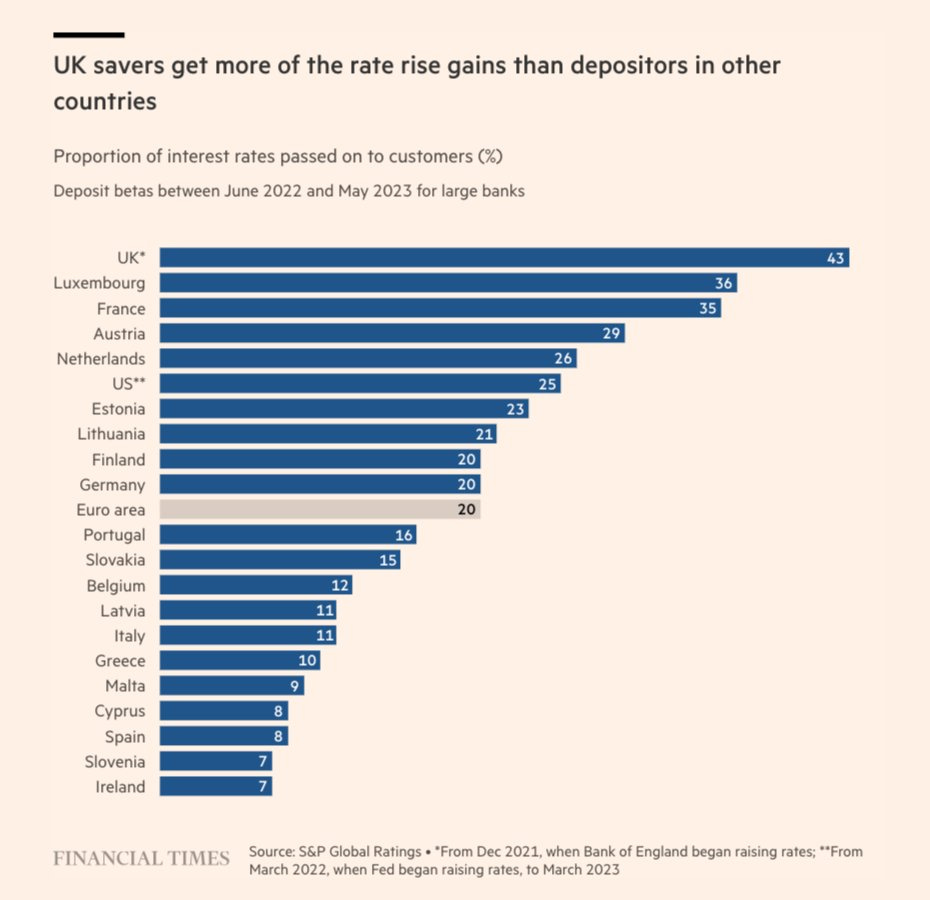

Recently, The Financial Times published a chart which explored the return customers across 20 European countries are making on bank deposits in the high interest environment. On top was the United Kingdom. At the bottom was Ireland and Slovenia. This in spite of the fact that the banks here are in fact making bank: AIB posted net profit of well over €800 million for the first half of the year, up by close to 80 per cent from the same period last year.

The Banking and Payments Federation (BPFI) has similarly recorded ‘a considerable surge in personal loan activity’ in the first half of this year, up by more than a quarter year on year, to well over €400 million.

For those unaware: banks make more money off loans when interest rates are high.

Despite the taxpayer forking €64 billion to save the banks in 2008 - AIB was given over €20 billion - they are not being served well in the here and now.

Revolut founder and CEO Nik Storonsky recently described Irish banks as “not good” when explaining why the FinTech has done so well in filling the void here.

Not good is an understatement; Irish banks have been maleficent.

While banks are forced by the ECB to carry more capital as a result of legacy issues arising from the crash this is no excuse to treat their customers so poorly in a highly profitable environment.

Indeed, with property prices set to fall and commercial property’s depreciating valuations increasingly appearing to be the canary in the coal mine as office space dwindles, the calls for an alternative structure to manage distressed assets, beyond overseas vultures, are growing.

Who will fill this role?

Is there a political appetite for a Nama 2.0?

Time will tell.